At the state level, the power to pardon or commute a criminal sentence-that is, to grant clemency-is vested in either the Governor, an executive clemency board, or some combination thereof. Until very recently, clemency grants were a consistent feature of our criminal justice system. In the last four decades, though, state clemency grants have declined significantly; in some states, clemency seems to have disappeared altogether. This Article contends that executive clemency should be revived at the state level in response to ongoing systemic criminal justice failings. Part I describes clemency at the state level today. Despite judicial and scholarly support for the role of clemency in our criminal justice system, state clemency practice fails to live up to its theoretical justifications. Part II makes the case for a policy of vigorous clemency on both theoretical and practical grounds. Not only was clemency designed, at least in part, to serve an error-correcting function, but also, today, there are several reasons why state executive actors may be able to use their clemency power robustly without suffering politically. Part III addresses questions of implementation. If state executive actors are to pursue commutations of sentences or pardons, which inmates should be the subject of such pursuits? How can those executive actors best be insulated from political pressure? In sum, this Article argues that revitalizing state clemency is a valuable and viable component of broader criminal justice reform.

Second Chances Resource Library

The Second Chances Resource Library contains resources related to expanding release opportunities

for people in prison who are serving long sentences or have other circumstances warranting release

Found 332 resources

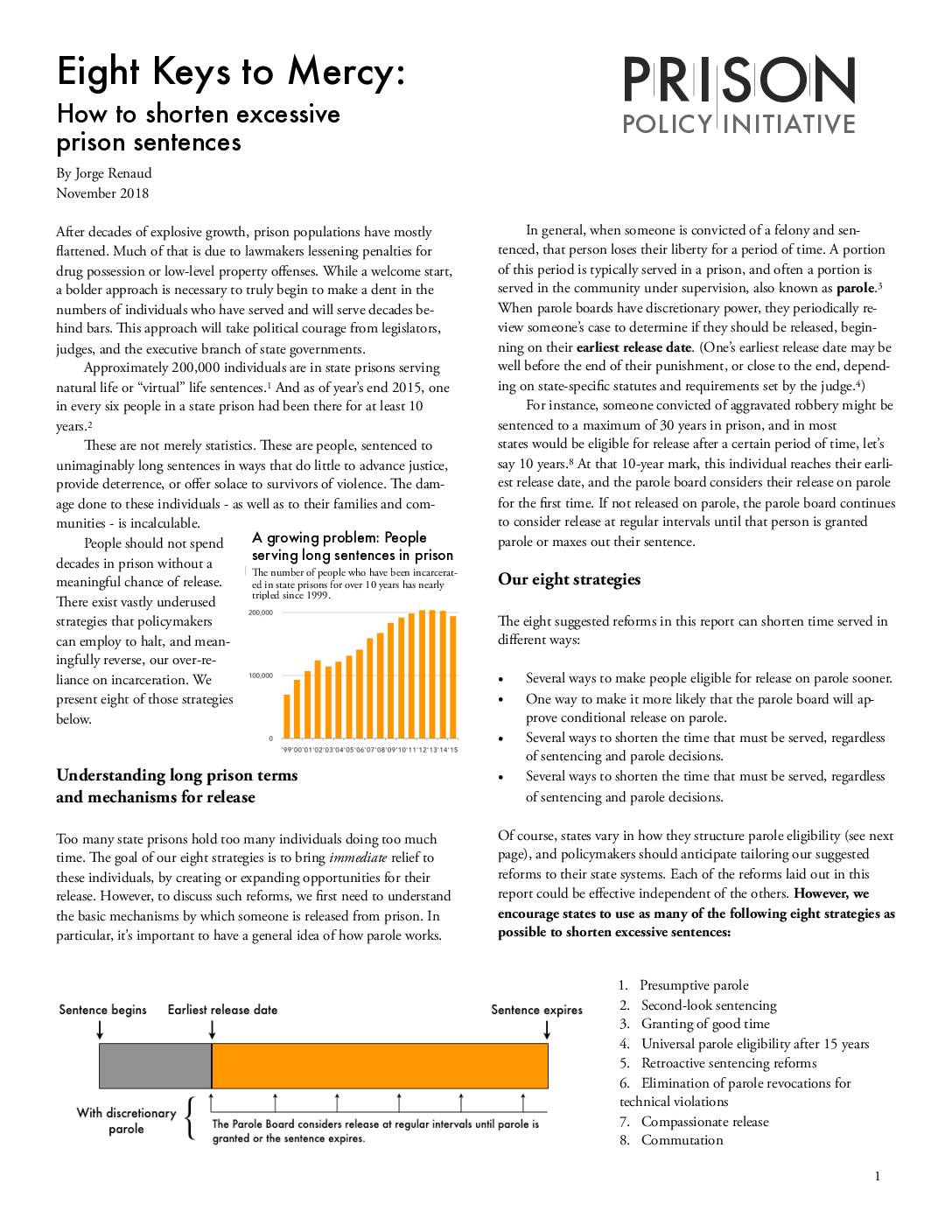

PDF Eight Keys to Mercy: How to shorten excessive prison sentences

This report encourages states to use as many of the following eight strategies as possible to shorten excessive sentences:

- Presumptive parole

- Second-look sentencing

- Granting of good time

- Universal parole eligibility after 15 years

- Retroactive sentencing reforms

- Elimination of parole revocations for technical violations

- Compassionate release

- Commutation

PDF A Matter of Time: The Causes and Consequences of Rising Time Served in America’s Prisons

People are spending more time in prison, and the longest prison terms are getting longer.

To better understand long prison terms, the authors of this report took a new approach to measuring how much time people spend in US prisons. They looked at annual snapshots of prison populations to see how long people had been in prison so far and compared those snapshots over time. This allowed them to include time served by people who are usually overlooked by more traditional methods.

Any amount of time spent in prison can feel long, but some terms are truly extreme. Because state policies greatly influence sentencing and release, we looked at the top 10 percent of people serving the longest prison terms in each state. We also tracked changes among people serving terms of 10 years or more. By either measure, the longest prison terms have been growing in both length and number.

PDF Time Served: The High Cost, Low Return of Longer Prison Terms

As discussed in this report, the length of time served in prison has increased markedly over the last two decades. Prisoners released in 2009 served an average of nine additional months in custody, or 36 percent longer, than offenders released in 1990. Those extended prison sentences came at a price: prisoners released from incarceration in 2009 cost states $23,300 per offender–or a total of over $10 billion nationwide. More than half of that amount was for non-violent offenders.

The report also found that time served for drug offenses and violent offenses grew at nearly the same pace from 1990 to 2009. Drug offenders served 36 percent longer in 2009 than those released in 1990, while violent offenders served 37 percent longer. Time served for inmates convicted of property crimes increased by 24 percent.

Almost all states increased length of stay over the last two decades, though that varied widely from state to state.

The report also summarizes recent public opinion polling that shows strong support nationwide for reducing time served for non-violent offenders.

PDF Long-Term Sentences: Time to Reconsider the Scale of Punishment

This article describes the origins and contours of the growing movement for justice and sentencing reform and assess its impact on the scale of incarceration to date. There are good reasons to be encouraged about these developments. However, it is also clear that at the current pace of decarceration, the cumulative effect of this movement will fall far short of what is necessary to achieve a more rational, compassionate balance in the justice system.

A key issue in assessing the decarceration trend is American sentencing policy and practice related to the length of prison terms. Defendants convicted of felonies in the U.S. are more likely both to be sentenced to prison and to serve more time in prison than in comparable nations. The excessive nature of punishment in the U.S. is not based on a rational analysis of incarceration and the fundamental objectives of sentencing policy. Moreover, unduly long prison terms are counterproductive for public safety and contribute to the dynamic of diminishing returns as the prison system has expanded.

PDF How Many Americans Are Unnecessarily Incarcerated

Nearly 40 percent of the U.S. prison population — 576,000 people — are behind bars with no compelling public safety reason, according to a new report from the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law. The first-of-its-kind analysis provides a blueprint for how the country can drastically cut its prison population while still keeping crime rates near historic lows.

PDF Prosecutor-Initiated Resentencing: California’s Opportunity to Expand Justice and Repair Harm

For The People’s 2021 report is the first to examine the origins, trajectory, and impact of Prosecutor-Initiated Resentencing. Through expert analysis of prison data, this report looks at how specific policies led to mass incarceration in California, reviews the evidence in support of releasing people who no longer need to be incarcerated, examines the opportunity for PIR, and shares the real impacts of resentencing on people who have already been released. Finally, the report offers recommendations on implementation and opportunities for further reform.

PDF Nothing But Time: Elderly Americans Serving Life Without Parole

This report investigates demographic, crime, and sentencing data of 40,000 people in 20 states serving life without parole (LWOP), which represents three-quarters of people serving LWOP nationally. The analysis shows that:

- 47 percent of people serving LWOP are at least 50 years old.

- 60 percent of the elderly imprisoned serving LWOP have already served at least 20 years.

- Half of aging people serving LWOP are Black and nearly 60 percent are people of color.

- One in 7 of the elderly LWOP population was under 25 at the time of their offense.

- In ten years, even if no additional LWOP sentences are added in these states, 30,000 people will be 50 or older.

Older people present an extremely low risk to public safety; imprisonment until their death is inhumane and represents ineffective crime prevention. The report recommends the following reforms:

- Allow immediate sentence review with presumption for release for those who are 50 and older and have served 10 years;

- Reinstate parole for those currently ineligible;

- Give added weight to advanced age at parole or sentence review hearings;

- Revise medical release statutes and policies to include persons sentenced to life imprisonment; and

- Expand clemency release opportunities.

Without intervention, the number of elderly people serving life without parole stands to increase substantially in the coming decade, and prisons are largely unprepared to handle their medical, social, physical, and mental health needs.

PDF Searching for Clemency in the Constitution State

This report examines the history and sharp decline of commutations in Connecticut.